fam = [1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]

fam = list((1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89))

fam[1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]In this lesson we will get to know and become experts in:

In contrast with tuples, lists are variable length and their contents can be modified in place. Lists are mutable. You can define them using square brackets [] or using the list type function:

fam = [1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]

fam = list((1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89))

fam[1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]You can sort, append,insert, concatenate, …

#sorting is in place!

fam.sort()

famfam.append(2.05)

famfam + fam[1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89, 1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]Lists can

fam2 = ["liz", 1.73, "emma", 1.68, "mom", 1.71, "dad", 1.89]

fam2['liz', 1.73, 'emma', 1.68, 'mom', 1.71, 'dad', 1.89]fam3 = [["liz", 1.73],

["emma", 1.68],

["mom", 1.71],

["dad", 1.89]]

fam3[['liz', 1.73], ['emma', 1.68], ['mom', 1.71], ['dad', 1.89]]

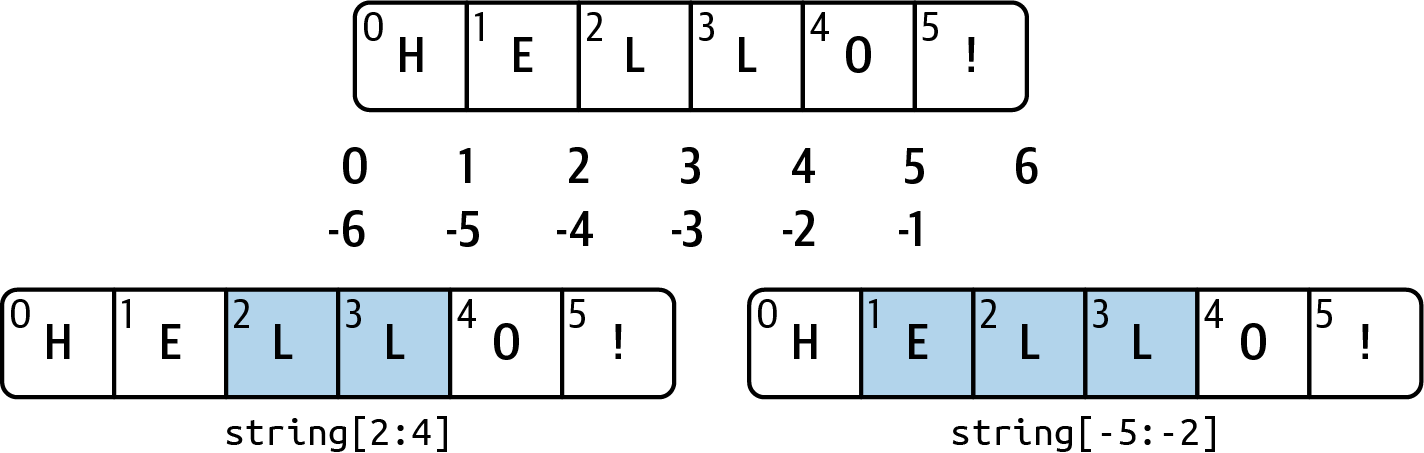

You can select sections of most sequence types by using slice notation, which in its basic form consists of start:stop passed to the indexing operator []:

fam[1:3][1.68, 1.71]

While the element at the start index is included, the stop index is not included, so that the number of elements in the result is stop - start.

Either the start or stop can be omitted, in which case they default to the start of the sequence and the end of the sequence, respectively:

print(fam[1:])

print(fam[:3])[1.68, 1.71, 1.89]

[1.73, 1.68, 1.71]Negative indices slice the sequence relative to the end:

fam[-4:][1.73, 1.68, 1.71, 1.89]Slicing semantics takes a bit of getting used to, especially if you’re coming from R or MATLAB. See this helpful illustration of slicing with positive and negative integers. In the figure, the indices are shown at the “bin edges” to help show where the slice selections start and stop using positive or negative indices.

The following list of lists contains names of sections in a house and their area.

house = [['hallway', 11.25],

['kitchen', 18.0],

['living room', 20.0],

['bedroom', 10.75],

['bathroom', 9.5]]for loops are a powerful way of automating MANY otherwise tedious tasks that repeat.

The syntax template is (watch the indentation!):

for var in seq :

expression

::: {.cell execution_count=23}

``` {.python .cell-code}

#We can use lists:

for f in fam:

print(f)

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

1.73

1.68

1.71

1.89

```

:::

:::

::: {.cell execution_count=24}

``` {.python .cell-code}

#or iterators

for i in range(len(fam)):

print(fam[i])

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

1.73

1.68

1.71

1.89

```

:::

:::

::: {.cell execution_count=26}

``` {.python .cell-code}

#or enumerate

for i,f in enumerate(fam):

print(fam[i], f)

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

1.73 1.73

1.68 1.68

1.71 1.71

1.89 1.89

```

:::

:::

### Iterators (Optional)

An iterator is an object that contains a countable number of values.

An iterator is an object that can be iterated upon, meaning that you can traverse through all the values.

Technically, in Python, an iterator is an object which implements the iterator protocol, which consist of the methods `iter()` and `next()`.

::: {.cell execution_count=5}

``` {.python .cell-code}

mytuple = ("apple", "banana", "cherry")

myit = iter(mytuple)

print(next(myit))

print(next(myit))

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

apple

banana

```

:::

:::

::: {.cell execution_count=6}

``` {.python .cell-code}

mystr = "banana"

myit = iter(mystr)

print(next(myit))

print(next(myit))

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

b

a

```

:::

:::

Strings are also iterable objects, containing a sequence of characters:

::: {.cell execution_count=4}

``` {.python .cell-code}

#funny iterators

print(range(5))

list(range(5))

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-stdout}

```

range(0, 5)

```

:::

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-display execution_count=4}

```

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

```

:::

:::

1. Repeat the tasks 2 and 4 from above by using a for loop

- using `enumerate`

- using `range`

2. Create two separates new lists which contain only the names and areas separately

3. [Clever Carl](https://nrich.maths.org/2478#:~:text=Gauss%20added%20the%20rows%20pairwise,quantity%20in%20a%20clever%20way.): Compute

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{100}{i}

$$

::: {.cell execution_count=27}

``` {.python .cell-code}

```

::: {.cell-output .cell-output-display execution_count=27}

```

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

```

:::

:::

### Conditions

The syntax template is (watch the indentation!):

if condition: expression

for f in fam:

if f > 1.8:

print(f)1.89if inside a for loop